CHAPTER 15 THE VIJAYANAGAR-BAHMANI COMPLEX : INDIA, HINDUTVA AND HISTORY

CHAPTER 15: THE VIJAYANAGAR-BAHMANI COMPLEX

|| Understanding medieval South Indian kings as competitors and collaborators-“Hindu Age”, a misnomer-rise of Bahmani-Vijayanagar in tandem-Zafar Khan and Kapala Nayaka ally against Tughlaq-Delhi Sultanate is expelled from the Deccan-alliances between Bahmani Sultanate and surrounding Hindu rajas-Vijayanagar expands by defeating Hindu kingdoms-Hindu orthodoxy opposes Hakka and Bukka || rise of the hybrid Dakkhani figure || balance of powers between Bahmani Sultanate, Vijayanagar and Warangal-cross religious alliances and intra-religious hostilities-alliance between Deva Raya of Vijayanagar and Feroze Shah Bahmani-alliance between Bahmani rebels and Bukka Raya of Vijayanagar-conflict between Reddys and Vijayanagar-rising aggression by Kalinga against Vijayanagar and Telugu Velamas || medieval South India as a global and local arena of opportunity and upward mobility-rise of governors of Hindu origin in Bahmani Sultanate || fall of the Madurai Sultanate || internecine strife in the House of Vijayanagar || Afaqi against Dakkhani, and other divides in the Bahmani Sultanate ||

In 1346, Zafar Khan returned to the Deccan from

Afghanistan to join the fighting against Tughlaq in Gulbarga. The Kapala Nayaka

of Warangal joined him (484). At the same time, the Sangama brothers gathered

at Sringeri Matt in Mysore to declare themselves rulers in the former Hoysala

lands (483). The Sringeri Matt, led by the priest Vidyaranya, performed a

“vijayotsava” (victory celebration) for Hakka and his brothers.

Early the following year, 1347, the Delhi Sultanate

was expelled from the Deccan, and Zafar Khan was crowned “Sultan Bahman Shah”.

Thus formed the Bahmani Sultanate.

Zafar Khan had been a senior general in Khilji’s

armies and probably came from an aristocratic family with connections to

“Bahman”, a legendary king of that name in Iran. There is also a legend that he

was originally either a Brahmin himself or served one, and that the name he

took was a corruption of “Brahmin” (485).

The Bahmani Sultan shifted the capital from Daulatabad

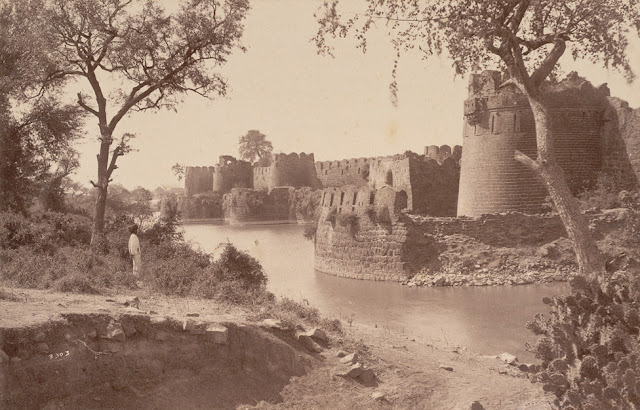

to Gulbarga. The Sangamas named their capital Vijayanagar (today known as Hampi).

The Sangama brothers ruled as joint kings. This was a model that was also in vogue among the Pandyas and Cholas in early medieval Tamil country, where the kingdom would be divided among the brothers of a family, and all would have the title of king.

The Bahmani Sultanate extended over Maharashtra,

Telangana, and Karnataka to the River Krishna to the south. Later, in the

mid-1400s, it extended further south to Trichy, and further north to Odisha. The

Vijayanagar Kingdom comprised of all the territories that they had brought under

their suzerainty from the Hoysalas and Tamil rajas south of the Krishna River.

Sultan Bahman Shah’s first task was to consolidate his

hold over as much as was possible of the fallen Tughlaq Sultanate in the Deccan

(487). To begin with, he left the Vijayanagaris alone, as did they leave him

alone, except for skirmishes here and there. For the rest of the territories, Bahman

Shah adopted the policy of using diplomacy to its fullest before going to war

with any of the sitting Hindu rajas.

When he found that he would have to send in his army,

the men were given strict instructions to avoid loot and plunder, leave

civilians unharmed, assure Hindu landowners of their holdings, and to accept

alliances where they were offered. In some places, his generals returned

properties that had been looted or confiscated in the course of the campaign

against Tughlaq. The strategy worked well, and many rajas who had accepted

tributary alliances with Tughlaq accepted Bahman Shah’s suzerainty without a

fight.

Bahman Shah divided his kingdom into four provinces or

“tarafs” – Gulbarga (northern Karnataka), Daulatabad (Maharashtra, former Deogarh),

Bidar (northern Karnataka) and Berar (Maharashtra). Each province was ruled by

its own governor.

Kapala Nayaka remained ruler of Warangal, subject to

payment of tribute and the handover of the Koulas Fort to the east of Bahmani

territories (488). We shall note here as ever after in the Bahmani-Vijayanagar age, that contrary to the communal colour given to events here today by the

adherents of Hindutva, the Telugu Nayakas chose to ally with the Bahmani Sultan,

and not their religious and probably ethnic (Telugu) compatriots, the Sangamas.

The Sangama brothers remained in possession of their

territories, except for the annexation of the Raichur Doab by Bahman Shah two

years into his reign. The Raichur Doab was a fertile stretch of triangular land

spread over today’s Telangana and Karnataka, where the Krishna and Tungabhadra

rivers met. It was coveted by all the kings and chieftains of Karnataka-Andhra

country. Generations of them fought over the Doab, one after the other.

Tughlaq’s equal unpopularity with Hindus and Muslims helped Bahman Shah. Former allies of Khilji, such as the Hindu Mewar rajas, came to his aide, as Bahman Shah was known to have been a Khilji loyalist (489).

Deeper south, the Sangama brothers kept the chiefs and

local rajas that had been allied with the Hoysalas in place. So Tamil country

continued under the direct rule of Chola and Pandya rajas.

Considering that both the Bahmani and Vijayanagar

kingdoms were in their early and untested days, it is noteworthy that neither

side attacked the other immediately. Usually, the rise of a new king,

especially one that has overthrown a previous powerful regime, was taken as an

opportunity to attempt to dominate him.

I am convinced, though this is never said, that the

Sangama brothers and Zafar Khan rose in league with each other. Let us not

forget that the Hoysalas were allies of the Tughlaqs. It would have made sense

for Zafar Khan and the Sangamas to have formed a counter-alliance, the former taking on Tughlaq’s

Deccan holdings, and the latter taking on the Hoysala’s.

Moreover, Harihara Sangama and his brother, Bukka Raya,

were among the Dakkhani Hindu warrior chiefs who had served Tughlaq. As we saw

in Chapter 14, Harihara and Bukka Raya had been appointed “amirs” by Tughlaq.

This means that it is likely that they would have been well-acquainted, and

even on congenial terms, with Zafar Khan as a fellow distinguished member of

the Delhi Sultanate’s establishment in the Deccan.

As we read in the previous chapter, Zafar Khan was

given an iqta by Tughlaq after distinguishing himself in the war against

Kampili, where Hakka and Bukka are said to have served. Zafar Khan may have

brokered the agreement between them and Tughlaq, which saw the Sangama brothers appointed as

amirs and given the charge of Kampili.

No historian appears to have explored this possibility

of a Bahmani-Vijayanagar compact. There is a tendency to view the Bahmanis and Vijayanagaris

only as adversaries. They were, but their history also shows periods of

alliance and friendship. I believe that they, as with their predecessor kings

in the Deccan theatre, are better understood as competitors than enemies.

Nilakanta Sastri says that the Sangama brothers served

in the armies of Pratap Rudra of Warangal, and moved to Kampili when Warangal

was defeated by Delhi. He says, that when Kampili fell, Hakka and Bukka were

taken as prisoners to Mohammad bin Tughlaq in Delhi, where they won his favour

by embracing Islam (491).

However, it is doubtful that Hakka and Bukka in fact

espoused Islam, or even went to Delhi. They do not appear to have been recruited

as slaves. If they had been serving in the Warangal armies, they would have

been a bit too old in age for that.

As we will see, besides slave-recruitment, the sultans

of the Deccan also had a system of engaging soldiers without requiring

conversion. Under the later Deccan sultans and Vijayanagar rajas we see Hindus

being employed in the sultans’ armies and Muslims in the rajas’, without anyone

being required to change their faith.

Hakka and Bukka belonged to a powerful local clan, and stayed very much in touch with each other as a family. This was not how slave-recruitment worked generally. Slave recruits were completely absorbed into the organisation and culture of the army and court, and did not retain their filial and social networks of origin.

Moreover, Tughlaq gave Hakka the high designation of

“amir”, and later appointed him and Bukka governors of Kampili. These facts

indicate that it is more likely that the brothers, as warrior chiefs with their

own men, were offered an alliance by Tughlaq in Kampili or an earlier Delhi

Sultan, in the course of Delhi's dealings with Pratap Rudra.

In either case, service under the Sultan, whether in

Delhi or Daulatabad (Tughlaq’s Deccan capital) could explain the very North

Indian sounding sobriquets of the Sangama brothers: “Hakka” and “Bukka”.

“Hakka-Bukka” is a Hindi expression that means to be stunned

or confounded. It may have been used in the Hindavi of the Delhi Sultanate

days. Perhaps the two brothers had acquired a reputation for stunning or

amazing their adversaries in combat, or the name, which consists of two paired

words, was simply picked as the brothers were also a pair.

According to Sastri, after Hakka and Bukka were

recruited into the service Tughlaq, the Hoysalas invaded Kampili and Tughlaq deputed

the Sangama brothers to restore order there in view of their having previously

served there.

From this point on, we see Hakka, Bukka and the rest

of the Sangama clan steadily acquiring Hoysala lands, without the Hoysalas

offering any challenge or resistance.

The Hoysalas had been in perpetual war with the

Yadavas of Maharashtra in the north, and intermittent battles with the Pandyas

in the south. They may have been hoping that the alliance with Tughlaq would

keep them going against their southern neighbours, and so tolerated the growing

assertiveness of the Sangamas.

Sastri says that apart from Gutti in Bidar (northern

Karnataka), Hakka and Bukka faced some resistance from the populace at the

start owing to their having been considered to have become Muslim. He says that

the brothers had to turn to an enterprising priest in the Sringeri Matt,

Vidyaranya (mentioned at the start of this chapter), to be “converted” back to

Hinduism.

But this is to put the gloss of 20th

century communalism on the events of the 14th century. Muslim governors

and sultans had faced no such popular resistance on religious grounds elsewhere

in the Deccan. In fact, Hindus and Muslims allied against Tughlaq, as we have

seen.

Even later, there was no resistance by the Hindu

populace on religious grounds to Deccan Sultans, such as Ahmad Nizam Shah, who

founded the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, and Fatullah Imad ul Mulk, who founded the

Berar Sultanate.

Both of them are said to have had Brahmin origins.

Ahmad Nizam Shah’s father, Malik Hasan Bahri, and Fatullah Imad ul Mulk, were

believed to have been captured in battle as boys by a Bahmani Sultan and

converted to Islam.

As we will see, the Vijayanagaris were also amenable

to contracting matrimonial alliances with the Deccan Sultans, and hosted them

in their lands. They also had mixed Hindu-Muslim armies (492). So it is likely

that Sastri is incorrect both about Hakka and Bukka’s having converted to Islam,

and to any resistance against them rising to become rajas in their own right on

these grounds.

It is true that the Sringeri Matt came into prominence

under the Vijayanagar rajas, even though it was supposed to have been founded

over half a millennium earlier by Adi Shankaracharya. It is also true that the

Sringeri Matt and the rulers of Mysore became closely associated with each

other since the Vijayanagar era.

Even the Muslim ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, is said

to have patronised the Sringeri Matt, and made repairs when it was attacked by

the Marathas.

From this matrix of facts and circumstances, an

interesting possibility emerges about Hakka and Bukka. Even before the arrival

of Khilji, we have seen that the Deccan was a chessboard of competing rajas,

with ever shifting alliances, intermarriage between dynasties, and a

multi-religious, multi-ethnic and multilingual courtly ethos. With the arrival

of the Sultans, this extended to the language, religion and culture of the

Delhi Sultanate.

Even before Khilji’s Dakkhani expeditions, South India

was well-familiar with Islam and Arabs from their extensive sea

trade since ancient times. There were already Arab settlements in the ports

since even before the founding of Islam. After the establishment of Islam, the

Arabs brought their new faith, along with mosques and sufis to the shores of

South India.

Rashtrakuta and Chalukya suzerainty over the coasts of

Gujarat led to close trade ties with the Muslim world, which was especially valued

for its horses. Arabs were given charge of ports in Gujarat under the

Rashtrakutas, and were also to be found in senior positions at Chola and Pandya

ports (60).

These social and economic conditions were ripe for the

emergence of a hybrid identity, an early version of today’s secular Indian,

comfortable in many worlds, free of insularity about whatever religious or

cultural tradition anyone was born or raised in; having close inter-communal

friendships and inter-communal courtly, professional and commercial alliances;

and generally au fait with the literature, arts, etiquette and

eccentricities of the many worlds they occupied.

All the pieces of the puzzle of Hakka and Bukka’s

origins fall into place if we consider them from this angle. They came of good

warrior-chieftain stock, and were in contention, as were others similarly situated,

to rise to high power and status in the Deccan of their times.

Warrior chiefs, generals and governors taking over a

kingdom was, as we have seen, an ancient pattern that stretched back to

pre-Mauryan times everywhere in India; and Hakka and Bukka were amirs of no

lesser power than the Delhi Sultanate in the Deccan.

For ambitious and able military men of warrior lineage like Hakka and Bukka, the coming of the Sultans to the Deccan might not have merely signalled a threat to temples and idols, which is how too many Tamil historians of the early 20th century have tended to see it, but to have extended the chessboard of their ambitions, which would thus far have been confined to the Deccan and, perhaps, Central India, all the way up to Delhi.

The rallying to the Sangama flag of Vidyaranya, through the organisation of a spectacular and highly publicised Hindu yagya for the brothers, might have been necessitated because in their cosmopolitanism Hakka and Bukka were a bit ahead of the times for the more orthodox among their Hindu subjects in the deep south of Karnataka.

Hakka and Bukka may have realised that while the common

people could understand a Hindu raja or a Muslim sultan, or even a Muslim sultan

who was a convert with Hindu origins, they were confused by a ruler that was neither

clearly Hindu nor Muslim.

The Sangama brothers responded intelligently to the

predicament. They nipped any controversy in the bud by getting the endorsement

of a respected and credible figure among their Hindu subjects in the form of Acharya

Vidyaranya.

The Sringeri Matt in turn probably recognised the

talent and ability of the Sangamas, and were happy to extend their endorsement,

especially in view of any apprehensions they may have had, for reasons real or

imagined, of the consequences of a Bahmani expansion into southern Karnataka

(493).

The Sangamas divided their kingdom into provinces

called “rajyas”, each placed under a subordinate prince or governor (494).

In the meantime, in Madurai, a succession of rulers

followed Sultan Dhamghani, whom we read about in the previous chapter. Finally,

in 1352, one of the Vijayanagar rajas, Kumara Kampana, the son of Bukka Raya,

fought against the reigning Sultan of Madurai, Shamsuddin Adil Shah, and killed

him (490).

But Kumara Kampana could not immediately take Madurai for himself. The Madurai nobles invited the Bahmani Sultanate to take

over. A nephew of Sultan Bahman Shah, Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, was installed on

the throne.

Kumara Kampana moved again, and after several rounds

of fighting, in around 1372, was finally able to take the Madurai Sultanate

after defeating and killing Fakhruddin’s son.

Madurai thus became a principality of Vijayanagar,

with Kumara Kampana appointed as its governor.

Harihara died in 1357, and his brother Bukka succeeded

him. Bukka Raya had a long reign; there is a record of him sending an

ambassador to the Ming Emperor in China in 1374 (486).

Over the decades to follow, the Bahmanis and

Vijayanagaris fought each other intermittently, especially when a new king was

crowned in the Sultanate. But the border between the two kingdoms never

changed. Clearly, the two powers were equally matched.

As mentioned earlier, both Bahman Shah and the

Vijayanagar rajas had mixed Hindu-Muslim armies. At the time it was believed

that Turks, Arabs, Afghans and North Africans made the best soldiers, so both

the Vijayanagris and the Bahmanis recruited them in large numbers from abroad.

These were both mercenaries and Turko-Persian

slave-soldiers who came to India via sea and land from Central Asia, Turkey, Khurasan,

Arabia, and so on.

Those coming on the land route tended to go to the

Delhi Sultanate, so the South Indian kings relied on the sea route for their

supply.

As a consequence, the port of Goa was of great

importance to both the Vijayanagaris and the Bahmanis. To begin with, Goa was

under the Vijayanagaris, who held it through a Muslim subsidiary. We will

return to matters in Goa later in this paper.

The newly arrived soldiers in the Deccan, called the “Afaqis”,

were resented by the “Dakkhanis” who were the older Muslim soldiers and nobles

who had come here and served under the Khiljis (495).

This division plagued the Bahmani Sultanate from start

to finish, and was a major factor in its ultimate downfall. The divide was

exacerbated by religious hostility – the Afaqis tended to be Shia, while the

Dakkhanis were mostly Sunni.

There was also a linguistic divide between the Persian-speaking

Afaqis and the Dakkhani language of the others. The latter consisted of the

Hindavi of Delhi that came with the Khiljis and Tughlaqs, with loan words from

the languages of the Deccan.

Dakkhani is spoken in Telangana till today, and is one

of the enduring legacies of Sultanate rule in the region, as are the languages

of Hindi and Urdu that grew out of Hindavi in the North.

In addition to the Arabs, Turks, Persians and Mongols,

North Africans also came to the shores of the Deccan as slaves and mercenaries (496).

They were Sunni, and tended to side with the Dakkhanis in the hostilities with

the Afaqis.

Since the early 13th century, when Sultan Mohammad Ghuri was assassinated after dividing his possessions in North and East India into governorships among his ablest officers, there were massive rifts between the Turko-Persians and Afghans there, which travelled with them to the Deccan. The appearance of African-origin warriors and courtiers created another ethnic fault-line in the politics of the Bahmani Sultanate. Later, divisions arose between the Mughals nobles in South India and the Deccan Sultanate courtiers.

Bahman Shah was succeeded in 1358 by Muhammad Shah I. The

Vijayanagaris and Telangana raja tried to obtain new terms from him (497). They

stopped paying tribute and asked for the return of the Koulas Fort and Raichur

Doab. They even threatened to ally with Delhi against him (498).

Kapala Nayaka formed an alliance with the Muslim

governor of Daulatabad in a challenge to the new Bahmani Sultan. Kapala

Nayaka’s son, Vinayak Deo, began to disrupt the sale of Arab horses to the

Bahmani Sultanate, the trade-route for which went through his lands (499).

Muhammad Shah retaliated by declaring war against both

the Nayaka and Bukka Raya (500). Both were defeated. Vinayak Deo was killed. But

Muhammad Shah also suffered heavy losses, and did not attempt to oust either

Kapala Nayaka or Bukka Raya.

The Bahmanis, Vijayanagris and Kapala Nayaka were evenly

matched. Though they never stopped trying to take territories from each other,

all three seem to have adopted the policy of making terms after testing their

chances of expansion on the battlefield from time to time.

Muhammad Shah’s treaty with Kapala Nayaka included the

gift of a marvellous ebony throne studded with precious stones (501). It came to be known as the “Turquoise Throne”

and became the symbol of the Bahmani Sultanate thereafter. Kapala Nayaka also

surrendered Golconda to Muhammad Shah.

Mohammad Shah’s terms with Vijayanagar recognised the

Krishna River as the southern boundary of his own Bahmani lands, with Bahmani

control being retained over the Raichur Doab. The treaty between Mohammad Shah

and Bukka Raya also included an agreement that they and their successors would

not kill non-combatants in future battles (502).

Muhammad Shah I was succeeded briefly by Alauddin

Mujahid Shah. Sultan Alauddin went to war with the Vijayanagar raja, but was

not able to dislodge him. Three years into his reign Alauddin Mujahid Shah was

assassinated. He was succeeded by Sultan Muhammad II who followed a policy of

peace with Vijayanagar.

This was a period of hostilities among the Nayakas in

Andhra country, as also between the Nayakas and the Vijayanagar kings. Again,

it is worth noting, that these intra-Hindu hostilities and wars belie the

Hindutva presentation of the Vijayanagar kingdom as a “Hindu” bulwark against

Muslim rule in South India.

The Telugu Velama chief of Rajakonda, called Anapota,

attacked and killed Kapala Nayaka in 1369 (503). Bukka Raya II, the son of Harihara,

attacked Anapota. In turn Anapota allied with the Bahmanis to hold the

Vijayanagaris and Reddys at bay.

Vijayanagar was able to annex Goa and other ports in

the north-west. They also took the possessions of the Reddys of Kondavidu in

the coastal Andhra areas of Nellore and Guntur, and Kurnool, which was near

Vijayanagar lands on the Tungabhadra. Virupaksha of Vijayanagar also invaded

Ceylon (Sri Lanka), placing it under tribute (503).

Muhammad II died after twenty years on the throne. There

followed a series of bloody intrigues and short-lived Bahmani Sultans, which

ended with the rise of Feroze Shah in 1397.

Seeing the instability in the Bahmani Sultanate,

Harihara II of Vijayanagar went on the attack with the idea of annexing the

Raichur Doab (504).

Feroze Shah was able to hold on to the Raichur Doab,

but not by defeating Harihara II in battle. He tricked Harihara’s son, who was

leading the Vijayanagar forces, by sending into his camp some of his officers

disguised as street performers.

They killed the Vijayanagar prince. Chaos broke out,

and the Vijayanagar armies were overwhelmed. But Feroze Shah agreed to terms

with Harihara II, probably knowing that he could not beat Vijayanagar in a

full-scale war.

Peace reigned between Vijayanagar and Bahman for the

next 6-7 years, even though Harihara stopped paying the agreed tribute to the

Bahmanis after entering into an alliance with the Muslim rulers of Gujarat,

Malwa (Madhya Pradesh) and Khandesh (an important principality on the Maharashtra-Madhya

Pradesh border) (503).

These sultans had been annoyed by Feroze Shah having

sent tribute to Timur, who had raided North India in 1398, reaching as far as

Delhi (505). Feroze Shah had obtained a declaration from Timur naming him, i.e.,

Sultan Feroze, the ruler of Gujarat and Malwa.

This declaration was meaningless, as Timur had exited

from India after the raid. But it disturbed the sultans of Gujarat, Malwa and

Khandesh enough for them to reach out to Harihara for an alliance to keep Feroze

Shah in check.

Another of many examples of inter-religious dealings

in the Deccan that give the lie to affairs there being a matter of Hindu-Muslim

contestation as claimed by the votaries of Hindutva.

Harihara II’s death in 1404 AD led to a succession

dispute in Vijayanagar. Feroze Shah seems to have decided not to take advantage

of the situation, staying within the borders agreed with Harihara II.

In 1406, Deva Raya defeated his cousins to take the

throne of Vijayanagar. Emboldened by alliances with the sultans of Gujarat and

Khandesh, Deva Raya tried, in the pattern of his forebears, to annex the

Raichur Doab (506).

Feroze Shah was able to drive him out of the Doab, but

again, the Vijayanagar raja held firm in his existing territories. There was a

stalemate that ended in a treaty.

Both sides seem to have determined upon a lasting

peace. Deva Raya gave a daughter in marriage to Feroze Shah. The open and easy

celebration of this match in Vijayanagar itself, with the wedding festivities

lasting over a month, indicates that its being a Hindu-Muslim marriage was not

in any way remarkable for the time (507).

It is more than likely that this alliance was taken as

of a piece with the long-standing example in South India of kings sealing

treaties with former rivals of different ethnicity and faith with marital

alliances.

The Reddys, who had lost lands to Vijayanagar, now

rose to take parts of Udayagiri in Nellore from them (508). Other Telugu

Nayakas, such as the Choda chief Anadeva, allied with Feroze Shah to keep his

lands between the Krishna and Godavari rivers.

Vijayanagar sought an alliance against Anadeva with

his brother-in-law, Katayavema, the Reddy chief of Rajahmundhry. Feroze Shah

intervened to defeat and kill Katayavema, but Deva Raya was able to capture the

fort of Panagal in western Andhra territory.

Deva Raya was also able to persuade the Velamas of

Rajakonda to break their alliance with the Bahmanis. Deva Raya and Rajakonda

invaded Kondavidu in Andhra country, and divided it between themselves, thus

ending the reign of the Reddys in that region.

Feroze Shah was not able to keep Rajamundhry, which

was re-taken by the dead Katayavema’s general. The general placed Katayavema’s

son on the throne of Rajamundhry (508).

Feroze Shah tried to invade Odisha towards the end of

his reign, but this impelled the Vijayanagar and Telangana rajas to unite

against him (510). The Bahmani Sultan appealed to the Sultan of Gujarat, who declined

to help. He was badly defeated.

Vijayanagar and Telangana chased Feroze Shah away, driving

him back into his lands. They are said to have left only after much plunder,

bloodshed and breaking of mosques.

Feroze Shah is remembered as a gifted man. He knew

many languages, and left a celebrated body of writing. He recruited Hindus both

into his administration and armies (509).

Feroze Shah was succeeded by his brother Ahmad Shah

who shifted the Bahmani capital to Bidar (Northern Karnataka) (511). A drought fell

upon the Bahmani kingdom at the time of Ahmad Shah’s reign. He is said to have

brought the rains by his prayers, and has since been revered in the region as a

sufi pir (512).

Ahmad Shah is said to have been much liked by his

Lingayat subjects. Till today, Hindus and Muslims come to pray at his mazhar in

Bidar, and the Lingayat priests of Gulbarga celebrate the urs (meaning union

with the Divine, as the death of a pir is traditionally referred to) of Ahmad

Shah here, wearing the robes and tall Persianate cap of the Sufi sheikhs (513).

It may be noted that this inter-communal tradition

grew around Ahmad Shah even though he attacked the Vijayanagar and Telangana

rajas (514). After his war with Deva Raya, Ahmad Shah returned with two Brahmin

boys among his prisoners-of-war.

They were converted to Islam, and drafted into his

armies. Both went on to have illustrious careers in the Deccan. They first

served as governors in various provinces of the Bahmani Sultanate. When the Bahmani

Sultanate declined, one of these Brahmin-origin slave soldiers, now known as

Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk went on to become Sultan of Berar.

The other Brahmin-origin officer was named Malik Hasan

Bahri. He rose to become Nizam-ul-Mulk of the Bahmani Sultanate. His son, Malik

Ahmad, founded the Nizam Shahi Sultanate of Ahmadnagar (512).

The question to be asked of the ideologues of Hindutva is what these two men must have made of their fate, which took them out of the obscure, humble life into which they had been born, to become powerful sultans.

The story of Malik Hasan Bahri’s career as recorded by the medieval Persian chronicler, Ferishte, is revealing of the treatment and opportunities given in the sultans’ armies to young slave-recruits such as him:

“Mullik Naib Nizam-ool-Moolk Bheiry, originally a

Brahmin of Beejanuggur [Bijapur? Vijayanagar?], whose real name was Timapa, the

son of Beiroo [Bhairav?]. In his infancy he was taken prisoner by the Mahomedan

army of Ahmud Shah Bahmuny, when, being admitted among the number of the

faithful, and having received the name of Hussun, he was brought up as one of

the royal slaves. The King was so struck with his abilities, that he made him

over to his eldest son, the Prince Mahomed (Muhammad III Lashkari), as a kind

of companion, with whom he was educated, and attained eminence in Persian and

Arabic literature. From his father’s name Beiroo, he was called Mullik Hussun

Bheiroo; but the Prince being unable to pronounce the word correctly, he

obtained the appellation of Bheiry. When the Prince ascended the throne, he

raised his favourite to the rank of a thousand horse……..

……In course of time he rose to the first offices in

the state, and was dignified by the titles of Ashraf Hoomayoon and

Nizam-ool-Moolk. Being a great favourite of the minister Khwaja Mahmood Gawan,

he was recommended by him to the government of Tulingana [Telangana], including

Rajamundry and Condapilly, which were granted to him in jageer. On the death of

that minister he succeeded to his office under the title of Mullik Naib and on

the demise of Mahomed Shah Bahmany he was appointed prime minister to that monarch’s

son, Mahmood Shah, who added Beer, and other districts in the vicinity of

[Daulatabad], to his estates (535).”

Ahmad Shah eventually made peace with Vijayanagar,

then ruled by Vira Vijaya, but ousted the Nayaka at Warangal in Andhra country.

Some years later there was an uprising in Warangal, and Ahmad Shah was forced

to replace his Bahmani governor there with a local Telugu chief as tributary.

This was the second time that the feisty Telugus had

refused to be ruled by a Sultanate-appointee. The first revolt had led to the

ouster of Tughlaq himself from Warangal, and catalysed his defeat in the Deccan

generally.

At this time, Deva Raya II was the raja in

Vijayanagar. He saw an uprising of farmers and artisans in his Tamil lands in

1429. The outcome was greater autonomy to the chiefs and rajas of Tamil

country.

This is another example of local concerns being at the forefront of affairs, and not any Hindu-Muslim divide as

portrayed by Hindutva readings of the history of Vijayanagar.

Ahmad Shah engaged in both cross-religious alliances

and intra-religious hostilities. One was his alliance with the Gondi Raja of

Kherla in Madhya Pradesh against the Shah of Malwa (515). He also persistently

attacked the Sultan of Gujarat.

Ahmad Shah consolidated relations with Hindu rajas in

the region and integrated Hindus into his service, but his reign saw the start

of internal strife between the Afaqis and Dakkhanis of the Bahmani court that

eventually brought about its downfall.

In a campaign that the Bahmanis lost against the

Sultan of Gujarat, the Dakkhani and Afaqi officers blamed each other (516).

Ahmad Shah was succeeded on the Bahmani throne by

Alauddin Ahmad II, the son of Feroze Shah. His younger brother conspired

against him, reaching out to Bukka Raya of Vijayanagar for help. Bukka Raya was

happy to step in if he could gain some advantage thereby (517).

The rebel prince and Bukka Raya together took a number

of forts and towns. But in the end Ahmad II prevailed. He forgave his brother,

giving him the jagir of the Raichur Doab (518).

It was a clever move, the jagir of the fertile Doab

was a rich one, and would, at the same time, keep the rebellious brother

occupied in defending against the constant incursions of the

Vijayanagaris!

Ahmad II’s reign saw a lot of drama. In an attempt to

gain access to the Konkan coast which was prized by all the Deccan rulers for

its port of Goa on which much trade, and also the passage of Haj pilgrims

depended, Ahmad II contracted a marriage with the daughter of the Konkan Raja Sangameshwar.

The Sultan fell deeply in love with his Konkani bride,

whom he named Pari Chehra (“Angel Face”) infuriating his senior queen, Agha

Zainab (519).

Zainab complained to her father, Nasir Khan Faruqi,

who was the ruler of Khandesh. Nasir Khan Faruqi came from an extremely

aristocratic line, connected to the Second Caliph. So he was able to garner the

support of a number of nobles against Ahmad II.

Ahmad II’s Dakkhani nobles advised him against

fighting the descendant of a Caliph. The religious element also played a role, as

the nobles were Sunni. Not to miss the opportunity to show up the Dakkhanis,

the Shia Afaqis then asked to be sent to fight Nasir Khan Faruqi, pointedly asking

that no Dakkhanis be sent with them (520).

The implication was that the Dakkhanis were not loyal

to the Bahmani Sultan. This infuriated the Dakkhanis, adding much fuel to their

long-standing enmity with the Afaqis. Nasir Khan Faruqui was defeated by the

Afaqis, and died soon after. His son, who succeeded to the throne of Khandesh, adopted

a policy of peace with Ahmad II.

The Bahmani Sultanate paid a heavy price for subduing

the small but prestigious principality of Khandesh with this episode. The

bitterness and distrust between the Dakkhanis and Afaqis reached such a pitch

that Ahmad II was compelled to physically separate them even in his court;

issuing orders that they assemble in separate groups to the right and left of

him when he held his Darbar (520)!

It was during the reign of Ahmad II that an

extraordinary man called Mahmud Gawan, a Persian, was brought into the Bahmani

Court (521). Gawan won the Sultan’s confidence and served three generations of

Bahmani rulers. However, as we will see, he came to a violent end as a casualty

of the enmity between the Afaqis and Dakkhanis.

In the meantime, Vijayanagar, now under Deva Raya II,

prepared for another war. The raja recruited vast numbers of Muslim

mercenaries, especially archers (522). An inscription of 1430 says that Deva

Raya had 10,000 “Turks” in his armies.

Muslims were now so large in number in Vijayanagar,

that Deva Raya II kept a Quran on top of a table in front of his throne so that

those presenting themselves to him could bow without violating the Islamic injunction

to only bow before God, and no man (522). Deva Raya II also allotted vast

estates in his kingdom to his Muslim commanders.

An idea of the communally hybrid culture of the time

can be gleaned from the dedication to the merit of Deva Raya II inscribed in a

mosque built in 1439 in Vijayanagar. The mosque was styled as a “dharma-sala”

or prayer hall, and built by one Ahmad Khan.

It was built in the form of a pillared hall similar to

the mandapas of the temples of the time, and did not have the domes or arches

typical of Islamic architecture (523).

Determined to add his efforts to those of his

predecessors in gaining the Raichur Doab, Deva Raya II launched an invasion

there. He managed to take the town of Mudgal at the edge of the Doab. But his

son was killed in the fighting, and the king himself died soon after (524).

Deva Raya was succeeded by his other son, Mallikarjuna.

At the time of Deva Raya

II, two Vijayanagari princes, Lakkana and Madana, were appointed governors of Tanjore

and Madurai, respectively (525).

Raja Kapileshwara of Kalinga (Odisha) had attacked

Rajahmundry in Andhra, which had held him off with the aid of Deva Raya II (526).

But upon the death of Deva Raya II, Kapileshwara of Kalinga took Rajahmundhry

and Udayagiri in Nellore, and the Bahmanis took Rajakonda from the Velamas.

The Velamas shifted their capital to Velugodu in

Kurnool in Andhra Pradesh. Kapileshwara now began raiding Vijayanagar’s Tamil

provinces of Trichy and Kanchi. He even raided Tanjore in the deep south. It may be noted that it was the Hindu

Kalingas and not the Muslim Bahmanis that attacked the Vijayanagaris at this

vulnerable moment (527).

Governors, Hindus again, appointed by the Vijayanagar

rajas also began asserting themselves. Saluva Gopa Timma, who had Trichy,

Tanjore and Pudukkottai in Tamil country declared independence. Saluva

Narasimha grew in influence in Chandragiri (Andhra country) (527).

The Konkan Raja Sangameshwar rebelled in 1447, and

Ahmad II sent a joint force of Afaqis and Dakkhanis to deal with him. They

quarrelled on the way and split, with the Afaqis being ambushed and massacred

by Sangameshwar.

The Dakkhanis sent messages to Ahmad II, making it

appear to the Sultan that the Afaqis had betrayed him. Ahmad II issued orders

for the Dakkhanis to execute the Afaqis. The Dakkhanis proceeded to massacre

the remaining unfortunate Afaqis who had survived Sangameshwara’s attack.

Eventually, the Dakkhani conspiracy was exposed, and

Ahmad II ordered their execution in turn. Miraculously, the Bahmani Sultanate

survived this awful saga of blood and betrayal (528).

When Sultan Ahmad died, a dramatic succession struggle

ensued between his sons Humayun and Hasan. Humayun managed to take the throne,

but nobles instigated Hasan against him a number of times. Finally, Hasan made

for Vijayanagar to seek asylum there. But he was caught and sent back to

Humayun, who had him killed by throwing him to a tiger (529).

Humayun was served well by Mahmud Gawan, the Persian

who had entered the Bahmani Court under his father, Ahmad Shah II (530).

Before Humayun died, as his sons were as yet young, he

appointed as co-regents the trusted Mahmud Gawan, and another senior courtier,

Jahan Turk (531). The division of responsibility between a Persian and a Turk

must have been with an eye to the communal divisions in the Bahmani court. The

co-regents were to act in consultation with the Queen Mother,

Mahmud Gawan and the Dowager Queen developed a close

relationship. She often stepped in to protect him when jealous Dakkhanis

intrigued against him. Gawan mentored the young crown prince, Muhammad Shah

III, and served him for many years when he grew up.

However, Jahan Turk did not fare as well as Mahmud

Gawan, and was eventually executed on charges of treachery on instructions of

the Dowager Queen (532). Going by his surname, Jahan Turk was likely a Dakkhani,

and though history remembers Mahmud Gawan as a noble statesman, the fate of

Jahan Turk may well have been engineered by him.

Under Mahmud Gawan, the Bahmanis were finally able to

conquer the Konkan coast, including taking Goa from the Vijayanagaris (533).

Another development at this time was a succession

struggle in Odisha after the death of Kapileshwara Gajapati. One of his sons,

Hamvira (Hambar) requested an alliance with the Bahmanis against his rival and

brother, Purushottam Gajapati (534).

Malik Hasan Bahri, one of the two Brahmins mentioned

above who were captured in boyhood by Sultan Ahmad, was sent by the Bahmanis to

help Hamvira. Bahri succeeded in installing Hamvira on the throne.

Hamvira in turn helped Bahri to bring under Bahmani suzerainty

the Reddys of Rajahmundhry and Kondavidu in Andhra country. Yet another of the

numerous examples of inter-religious alliances in the Deccan theatre.

Though Hamvira’s victory was short-lived, as

Purushottam soon managed to dislodge him, Malik Hasan Bahri rose in the

estimation of the Bahmani Sultanate for his handling of the affair in Odisha. He

was put in charge of Telangana.

As mentioned earlier, Malik Hasan Bahri’s son, Ahmad

Nizam Shah, went on to become the Sultan of Ahmadnagar. The other Brahmin origin

slave-recruit, Fathullah Imad-ul-Mulk, now a senior commander and noble, was

put in charge of Berar.

A few years later, the people of Kondavidu revolted

against their Bahmani governor. He was assassinated, and Raja Purushottam of

Odisha marched to take back his Andhra territories. He annexed Kondavidu and

attacked the fort of Rajahmundhry (536).

Purushottam was aided by Saluva Narasimha, the

governor of Chandragiri in Andhra country near Tirupati, who was then a

tributary of Vijayanagar (537).

Sultan Mohammad Shah III responded by himself coming

to fight in Telangana. It took him three years to regain control there. In the

course of this campaign, Mohammad Shah III also raided the Kanchi temple in

Tamil country, and captured the port of Masulipattinam (538).

The Dakkhanis continued to plot against Mahmud Gawan,

eventually persuading Muhammad Shah III that Gawan was conspiring with the Raja

of Odisha against him.

The Dowager Queen had died, depriving Mahmud Gawan of

his strongest shield against the Dakkhanis. Muhammad Shah III impetuously

executed Gawan, only to discover that he had been tricked. The stricken Sultan

collapsed, never to recover (539).

In the meantime, Raja Mallikarjuna of Vijayanagar had

died to be succeeded by his cousin, Virupaksha II. After the death of

Kapileshvara of Kalinga, Saluva Narasimha, the Vijayanagari governor of

Chandragiri, annexed Udayagiri in Nellore, expelled the Oriyas from other parts

of Andhra territory, and also captured Kondavidu and Masulipattinam (540).

Virupaksha II was murdered by his eldest son in 1485.

He was in turn killed by his younger brother, Praudha Devaraya, who now took

the throne. Saluva Narasimha saw the time was ripe for a takeover. He marched

on Vijayanagar, managing to enter the palace where he killed even some of the

women, and crowned himself king (541).

The Sangama dynasty at Vijayanagar had now been

replaced by the Saluva dynasty.

Though Hindutva ideologues speak of the “Vijayanagar

Empire” as though it were a single continuous dynasty, in fact, Vijayanagar saw

rule by four different dynasties, each succeeding the other after brutal

episodes of murder and betrayal.

The Sangama clan ruled from the 1330s to the 1480s.

The Saluvas from the 1480s to the 1500s. They were replaced by the Tuluvas from

the 1500s to the 1570s. The last dynasty to rule were the Aravidus, from the

1570s to the last quarter of the 1600s.

Though these successive dynasties are given the common

name of “Vijayanagar”, the city of that name (whose other name is Hampi) did

not even remain the capital of the kingdom. Towards the end of the Tuluva

reign, the centre of the kingdom had shifted from Karnataka to Penugonda, and

later to Chandragiri, both in Andhra country.

The last Vijayanagar capital was in Vellore in Tamil

country. It is also noteworthy that atleast three of the Vijayanagar dynasties

were not Kannadiga. The Saluva and Aravidu, were Telugu, and the Tuluva, were

Tulu.

According to some, the Sangama were also a Telugu

clan. The fact that we first hear of them in Warangal, indicates that this was the

case.

Saluva Narasimha was not popular in the Vijayanagar

kingdom. Feudatories of the ousted Sangamas rebelled, such as the Sambetas of

Kadapa in Andhra country, and the Palayagars of Ummattur near Mysore (542).

Vijayanagar’s access to Arab horses had been

interrupted by the annexation of Goa by the Bahmanis. In order to remedy this,

Saluva Narasimha invaded the Tulu region, spread over southern Karnataka and

northern Kerala, gaining access to a number of ports there. Kalinga’s

Purushottam Gajapati was able to re-conquer his Telugu territories from Saluva

Narasimha, who died soon thereafter (542).

In the meantime, the Bahmani Sultan Mohammad Shah put

Malik Hasan Bahri in charge of affairs at Bidar, the then capital of the

Bahmani Sultanate. Malik Hasan’s son, Ahmad, was appointed governor of

Daulatabad. Another Bahmani governor, Yusuf Adil Khan, took charge of Bijapur

and Belgaum, which included the sensitive port of Goa (543).

Soon thereafter Mohammad Shah died. His son and heir,

Mahmud, was only 12 years old, and the Bahmani Sultanate began to unravel.

Comments

Post a Comment