CHAPTER 8 DEVELOPMENTS IN HINDUISM IN EARLY MEDIEVAL SOUTH INDIA : INDIA, HINDUTVA AND HISTORY

CHAPTER 8: DEVELOPMENTS IN HINDUISM IN EARLY MEDIEVAL SOUTH INDIA

|| how Hinduism competed with other religions in South India-alvars and nayanars- Tamil Bhakti movement-emergence of priest ideologues-Adi Shankaracharya-Ramanujacharya-disputation and conflict with Buddhists and Jains-adoption of vegetarianism-conversion to Shaivism and Vaishnavism-conflict between Shaivites and Vaishnavites || multireligious ethos in legend and lore-Muslim princesses, Sulatani and Tulukka Nachchiyar idols and images in South Indian temples-Kabir and Jagannath Temple-Shreenathji of Nathdwara ||

Between about the 6th to the 11th century AD, a number of developments occurred in South India which had a profound impact on Hinduism all over the country. Tamil country was the epicentre of these developments.

Chief among these developments was the conversion to

Shaivism of well-known Jain monks, such as Appar, and of celebrated Jain kings,

such as Sundara Pandya of Madurai. These conversions occurred between the 6th

to 7th centuries AD. This was also the time when the Gangas, the

Jain rulers of Karnataka, were defeated by the Chalukyas, many of whose most

powerful kings espoused Hinduism.

The other major development was the rise of a series

of Hindu priests who were also brilliant thinkers and ideologues in the period between

the 6th to the 11th century AD, in particular Shankaracharya

and Ramanujacharya.

These scholar-priests had the same effect as Mahavir

and Buddha in earlier times in Indian society, sparking off a prolific

discourse, founding various schools of philosophy, and conducting debates up

and down the country. They also wrote commentaries on the Vedas and Upanishads,

and established “matts”, which were centres, usually associated with a temple, for

the study of Hindu thought.

This was also the period of the emergence of the Tamil

Bhakti movement whose primary element was devotional songs that were sung by

wandering monks called alvars and nayanars. They composed soul-stirring poems

to various Hindu deities and set them to beautiful music that won followers

everywhere. The Hindu tradition that grew out of these developments endures

till today.

Adi Shankaracharya

The first great thinker to appear on the scene was

Shankaracharya, also known as “Adi Shankaracharya”, who is said to have lived

in the late 8th to early 9th century AD. He was born in

Travancore (Kerala) (244). Shankaracharya is both praised and criticised,

depending on the point of view, for having evolved the doctrine of “Advaita”,

that aimed to syncretise Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Shakta-ism (245).

It was Shankaracharya who organised Brahmins into matts

around India modelled, according to Nilakanta Sastri, on the Buddhist sanghas (246).

The most famous of these matts, which exist till today, were founded at

Sringeri, Dwarka, Badrinath, Puri and Kanchipuram. This covers the north,

south, east and west of India. Some historians say that Shankaracharya did not

himself found these matts. However, regardless of which individual founded

them, they belong to the tradition that developed around Shankaracharya.

Shankaracharya’s doctrine, Advaita Vedanta, is

abstract and scholarly. It is not of the ecstatic devotional mode of Tamil

Bhakti. However, many impassioned Bhakti songs are attributed to him. These

songs have an iconic status among South Indians even today. An example is the

popular bhajan “Bhaja Govindam” which goes: “Remember Govinda! Remember Govinda!

O foolish one, empty repetition [of god’s name] will not save you!”

The tradition associated with Shankaracharya

significantly reduced the emphasis among Hindus on rituals, incantations and

caste taboos. There are many legends of Shankaracharya sharply criticising the

mindless practice of rituals or rote learning for young Brahmin students.

Concepts of “maya” – the world as an illusion; and

“brahman” – the objective reality underlying “maya”, were elaborated in

Advaita Vedanta, thus giving a place in Hindu spiritualism to abstractions

similar to the ones that gave Buddhism and Jainism their power at the time.

Shankaracharya is said to have defeated the Purva

Mimamsa school which had insisted on the “Karma Marga”, that is, worship

through strict adherence to ritual prescriptions. He is also said to have

accepted the wisdom of a “chandala” or outcaste who condemned caste taboos and

untouchability by pointing to the oneness and infinitude of all souls (254).

This is not to say that Advaita philosophy was

“all-inclusive” in the modern sense. Though Shankaracharya reduced the emphasis

on them, caste and rituals were never removed from the Hindu system, even

though it went through phases, and continues to do so till today, of the

alternate softening and hardening of caste-ist and ritual-ist thought and

practice.

The tradition of Shankaracharya is filled with legends

of him and his followers defeating and converting, often harshly, Buddhists and

Jains. His first tirth is said to have been to Prayaga expressly to rebut

Buddhist thought.

The hostility to Buddhism among Hindu ideologues at the time was so fierce that

Shankaracharya’s Advaita was criticised for being not sharp enough against it.

Ramanujacharya is said to have accused Shankaracharya of having been a covert

Buddhist!

While the intervention of Shankaracharya brought about

a re-orientation from ritual practice to a more abstract approach in Hinduism, as

mentioned above, ritualism was not entirely rejected here. In fact, temples and

idol worship, played an important role in the Shankaracharya tradition for the

advocacy of Hinduism. As explained in Chapter 7, the period starting the 6th

century AD was also the time when the building of Hindu temples came into vogue

in South India.

The repertoire of songs associated with the tradition

of Shankaracharya include various odes in praise of Durga and Shiva that use

the physical attributes of these deities as metaphors for their divine powers

in that superb combination of aesthetics, performance, philosophy and

spirituality that is the hallmark of Hinduism till today. The ancient Indian

performance arts belong to this tradition, and this is why they are also known

as the fifth Veda.

The powerful new philosophical ideas of Shankaracharya

and the impassioned devotional songs of the alvars and nayanars acted from

opposite ends as it were, one intellectual and the other emotional, to infuse

an irresistible new energy into Hinduism. On the one hand, Advaita Vedanta explained

and elaborated the philosophical elements of the Vedas and other Hindu

scriptures, showing Hinduism to be on par with Jainism and Buddhism as a doctrine

and moral code, and not simply a system of rituals, yagyas and “magical”

mantras.

On the other hand, the mode of worship of Tamil Bhakti

– an ecstatic union with the Divine through inspiring verse, music and dance,

exercised a power on the heart, mind and soul that we in India continue to feel

till today. For the Bhakti movement has never ended - it continues into our

times as a living tradition.

A very important element that contributed to this new

vitality in Hinduism in Tamil country was the use of Tamil as opposed to

Sanskrit, which had been the language of Hinduism, atleast for worship, till

then (248).

The singing alvars and nayanars would tour shrines and

temples spreading the new message of Bhakti with their songs. Sastri describes

these wanderings as “propagandist peregrinations” (247)!

Many historians of South India see the Bhakti wave in

Tamil country of the 5th and 6th centuries AD as a

conscious attempt by Hinduism to compete with Jainism and Buddhism. The Bhakti approach

held out a direct path to communion with God that was much more accessible to

ordinary people than the austerities and altogether more cerebral approach to spirituality

of Jainism and Buddhism.

PTS Iyengar says that the adoption of vegetarianism by Brahmins, which is not a Vedic requirement, also came from the need to make the Hindu tradition more acceptable to Jains. For the Jains, vegetarianism was a fundamental part of their ahimsa-based creed. Whereas Iyengar says that the Baudhayana Dharma Sutras permitted the consumption of meat by Brahmins, and the early “South Indian Brahmins of this period, like those of North India were meat-eaters (250)”.

The Apastamba Dharma Sutra, according to Iyengar,

permits the consumption of the meat of milch cows and oxen. He says that

according to the Apastamba the “Shradhs” should be performed in the second-half

of every month to please the manes and secure different kinds of rewards.

According to the Apastamba: “beef satisfied them for a year, buffalo’s meat for

a longer time, rhinoceros’ meat for a still longer time, also that of the fish

called satabali, the crane called vardhranasa (251).”

MS Ramawsami Ayyangar and B Seshagiri Rao also say

that Brahmins in Tamil country did not disdain the flesh of horses or cows

sacrificed in Vedic yagyas. They go on to speculate that the substitution of animal

models made of flour in place of actual beasts in Vedic yagyas may have been

under pressure from Jainism (252).

Many communities of Hindus were in any case

meat-eating, and remain so till the present times. For example, the Vijayanagaris

designated a special place in their Mahanavami festivities for the slaughter of

buffalo and sheep (253).

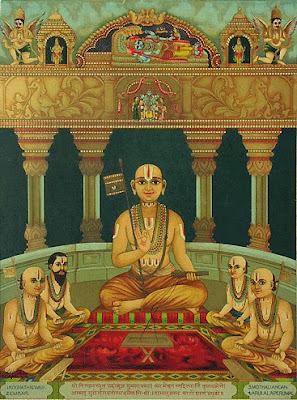

Ramanujacharya

The earthy and colourful Tamil Bhakti reached its

height under the Sri Vaishnavas, headed by Ramanujacharya in the 11th

century AD (255).

Ramanujacharya rose from the Shankaracharyite matts as

a challenger to Advaita Vedanta. He said that love, and not reason, was the

path to God. His gurus at Kanchipuram, all followers of Shankaracharya and

Advaita, were appalled….and somewhat helpless – for the brilliant young priest

made the case for a passionate embrace of the Divine with all the logic and

clarity of the coldest and dryest of Advaitics.

Ramanuja questioned, not quite everything, but enough

to shake things up quite dramatically in Tamil country. He said that caste

should not get in the way of understanding the Divine. By his time there were

brilliant non-Brahmin Vaishnavite-thinkers and accomplished non-Shaivite and

non-Advaitic Brahmin thinkers in temples and monastic orders all over South

India.

Ramanuja wanted the Advaitics to join them in thinking

about and reviving Hinduism. He was impatient with the taboos around inter-dining

and other interaction that inhibited a full exchange of ideas with thinkers from

other castes.

Ramanuja is said to have disagreed with the age-old tradition of keeping Hindu scripture secret within the priesthood. He also questioned why Pariahs - the outcastes and other so-called lower castes of the time - should not be given the same access to God through temples as any caste-Hindu.

There are many legends about Ramanuja having

experienced the kindness of Pariahs, which may be seen as the attempt by the

tradition that grew around him to persuade Hindu society to lower caste

barriers.

Ramanuja is said to have quarrelled with his wife over

his friendship with the Namboodiri Brahmins of Kerala. He thumbed the Shaivites

in the nose by joining the Vaishnavite temple at Srirangam as head-priest.

Ramanuja preached in Tamil and was enormously popular

with the common people. They gathered about wherever he went, and thronged the

precincts of Srirangam when he spoke.

His charisma and energetic advocacy of Sri Vaishnavism

won him followers and converts everywhere. Ramanuja is said to have assumed the

form of the thousand-headed Sesha Naga when worsting his hundreds of opponents

simultaneously in debate! Sesha Naga is the cosmic serpent on which Lord Vishnu

reclines, and which is said to hold the energy of the Universe that was

left-over after the manifestation of Vishnu at the dawn of creation.

But Ramanuja’s intervention, for all its brilliance and not inconsiderable nobility, was not without its problems. Legends of Ramanuja’s many enemies – the Jains in Karnataka after the Hoysala raja, Vishnuvardhana, was said to have been converted by him; the Shaivite Pandits of Kashmir, who are said to have been influenced by Shankaracharya, after the raja there was converted; the disappointment of the Shaivite worshippers in Tirupati (Andhra country) when Vishnu was chosen over Shiva - idols of both were said to be present at the temple there - as its chief deity; the priests of Jagannath who refused to adopt the form of worship advocated by Ramanujacharya; the Advaitics who are said to have tried to kill him – all reveal the division and turmoil that was created in the length and breadth of the country by the wave of Sri Vaishnavism set off by Ramanujacharya.

Even Lord Vishnu was said to have been perplexed by

the phenomenal success of his brilliant devotee. This is how the story goes:

When Ramanujacharya first knelt before the idol of Ranganatha at Srirangam on

the day that he took office as its head priest, the Lord is said to have told

him that He would now rest awhile, leaving the business of the Universe in his

exemplary devotee’s capable hands. Incidentally, the idol of Ranganatha depicts

Vishnu dozing on Sesha Naga.

Ramanuja then sets off on a tour of India converting

kings and commoners wherever he went. When he arrived at the Jagannath Temple

in Puri, Ramanujacharya confronted the first opposition to his hitherto

unchallenged tour of conversion all over India. The priests at the Jagannath

Temple, though they said nothing, looked decidedly mutinous as Ramanujacharya scolded

them to abandon their old ways and worship Jagannath in the manner he that had

instituted everywhere else. It may be noted that the Jagannath Temple is said

to have been built by a Ganga King, Indrasen or Indravarman. The Gangas were

Jain, and preponderantly built Jain temples. More study needs to be done on the

possible significance of this temple in Jainism.

Sensing the disagreement of the priests, Ramanuja

prayed to Lord Jagannath who appears before him. When you yourself commanded

me to carry out this work on Earth, then why do you not make the priests here

accept my way, complained Ramanuja. The Lord is discomfited. He

cannot deny that Ramanuja was carrying out the work He had asked of him. Yet,

as He tells Ramanuja, He liked the way He was worshipped at Jagannath and could

not Ramanuja leave things as they were in this one temple - he was free to

continue his work anywhere else!

Ramanuja went to sleep, determined to carry on the

discussion the next day. But the Lord pre-empted him by sending him off as he

slept to another land.

This is a very clever legend that tells us that our

ancestors have had to deal with religious revivalism and its consequences for

centuries. It also shows a deep awareness of the troubles that arise with too

zealous an advocacy of any creed in a land as diverse as India.

Ramanuja’s time seems to have been one of considerable

sectarian strife in Chola lands. The Vaishnavite tradition holds that Raja Kulottunga

Chola II was a zealous Shaivite who plotted against the increasingly popular

Ramanujacharya. The Ranganathaswamy Temple in Srirangam in Trichy from where

Ramanujacharya preached was at the time in Chola territory, and next to Tanjore,

which was a bastion of Shaivism.

Ramanujacharya fled to Hoysala territory in

neighbouring Karnataka where he is said to have converted the Jain king Hoysala

Vishnuvardhana to Vaishnavism. This, as noted above, caused much discontent

among the Jains in Hoysala territory.

In the meantime, Kulottunga II is said to have killed

and tortured Ramanuja’s disciples and destroyed a Vaishnavite temple in

Chidambaram, throwing its idol of Govindaraja into the sea.

Ramanuja returned to Chola lands after the death of Kulottunga

II. The Govindaraja idol is said to have been kept safe from Kulottunga II in

the Tirupati Temple in Andhra territory. The legend goes that Ramanuja visited

the temple, and had the idol installed in its own temple at the foot of the

Tirupati Hill, impressing the Raja of Tirupati, but not its Shaivites.

When Ramanujacharya returned to Srirangam, the entire town is said to have turned out to welcome him. Kulottunga III now sat on the Chola throne. Though he was the grandson of Ramanujacharya’s persecutor, he is said to have reconciled with the Vaishnavites.

But having settled with the Vaishnavites, Kulottunga Chola III appears to have got into trouble with the Shaivites. There is a legend that he killed a Brahmin whose ghost would haunt him. To atone for this, Kulottunga III visited all the Shaivite shrines in the land and expanded many Shiva temples in Tanjore and surrounding Chola lands. He is said to have finally gained release at the Tiruvidaimarudur temple, which has a hole in the wall of the sanctum from where the ghost left. The story is consecrated in stone with an image of the ghost at the temple’s east entrance.

The sectarian strife did not end here. Halfway through

the reign of Kulottunga III there was a famine during which he is said to have

“persecuted” some Shaivite monasteries by confiscating their properties (256).

All kings are accused of persecution and favouritism during famines, perhaps

the inevitable response to the austerities and scarcity of such times.

Kulottunga III appears to have required some Brahmins

to sell their lands for failure to pay taxes. He also gave over the

administration of a temple to the local community. These measures, arising

perhaps from the decline in the wealth of the Cholas or the famine, were resented

by the Brahmins.

There were also disputes in Kulottunga’s reign between

two clans called the “left hand classes” or “Idangaiyar” and the “right hand

clans”. They in turn had disputes with the Brahmin and Velala landowners of

Chola country.

How do we Indians make sense of our endlessly

fractious story? The answer may lie in the very legends of such conflicts

themselves: Ramanujacharya was so successful in converting the world to the

noble creed of Sri Vaishnavism, that the Chambers of Hell were bare, while

Vaikuntha (heaven) was crowded to excess.

Yama, the god of death, felt thwarted – there were no

souls left to be ennobled by the tortures he had devised for them in Hell! Mortals

had become so good that the Earth itself was looking to becoming a Heaven! Where

would Yama go if men were to become immortal?! And so, the gods went to Vishnu

to solve the problem that he had created by sending Ramanuja to Earth.

After listening to them Lord Vishnu said, the

balance of the Universe cannot be disturbed for any reason. And so, he sent

one of his servants to be born as Kulottunga Chola on Earth to restore the

imbalance created by Ramanuja! This was the Shaivite Chola king who is said to

have persecuted Ramanuja.

We can either choose to listen to the

wisdom of our ancestors, or ignore it…..

In this situation of legendary sectarian strife, there

is only one tale of communal amity. Brace yourselves for a surprise, as it

involves the Muslims: While Ramanuja was in the Hoysala kingdom, the freshly

minted Vaishnavite king, Vishnuvardhana, had a Vishnu temple built at

Ramanujacharya’s request. The Mula Vigraha idol – which remains inside the

temple at all times - was installed. But the temple lacked an Utsava Vigraha –

the second idol that all South Indian temples have, which is taken out in a

chariot and paraded through the main streets on festivals.

One night, the idol of Ramapriya came to Ramanuja in a dream. Ramapriya was a Vishnu idol of the Treta Yuga that Vibhishana had gifted to Ram. The idol got its name as Lord Ram was very fond of it - “Ramapriya” means “beloved of Ram”. In the Kaliyuga, the idol came into the Yadava dynasty (related to the Hoysalas) through marriage, and was installed in the fort at Melakote which was raided by a Muslim Emperor called “Tughlaq” or “Tulukka”. He had carried the idol off to Delhi, along with other plunder.

Ramapriya told Ramanujacharya in the dream that he

wanted to come back home. The next morning Ramanujacharya made for Delhi with a

Hoysala escort.

The Muslim Emperor is said to have himself come down

to Ramanuja’s camp on hearing of his arrival in Delhi. On being told of the

idol, the Emperor said that Ramanujacharya was welcome to retrieve it, and had

the royal vaults opened.

Ramanujacharya was not able to find the idol anywhere

in the vaults, and returned to his camp dejected. That night, Ramapriya appeared

before Ramanujacharya again in a dream, and said that he was in the rooms of

the Emperor’s daughter. She had developed a great love for him, and kept him

with her always.

Ramanuja went back to the Emperor who went with him to

his daughter’s chambers. Miraculously, the idol came gambling out, jumping into

Ramanujacharya’s arms as a child to its father. Astonished, the Emperor told

Ramanujacharya that he had better leave Delhi lest what he had just witnessed

were to weaken his own faith!

So Ramanujacharya left with the idol. But the

Emperor’s daughter insisted on following him as she craved Ramapriya. Escorted

by her brother, she caught up with Ramanujacharya and asked to get into the

palanquin that was carrying the idol.

After a while, the bearers noticed that the palanquin

felt lighter. When they looked inside, they found that the princess had

disappeared. So great was her love for Ramapriya, that her entire being had

dissolved into it. Ramanuja had the idol of Ramapriya installed with a golden

image of the Sultani at its feet in the temple at Melakote.

What is this legend about? Did it grow from marriage

alliances that were conducted on the arrival of the Delhi Sultanate about a

century after Ramanuja in the lands of the Hindu rajas? It is interesting that

the Ramapriya idol is said to have originally come to Karnataka as the dowry of

a Yadava princess.

Another version of the legend says that the princess

who came from Delhi was married to Ramanujacharya’s son. Were the followers of Ramanujacharya

then not the Hindu ideologues of legend, or despite being so, actively involved

in forging acceptance of the Hoysala alliance of the 14th century

with the Delhi Sultanate, and of integrating Muslims and Islam into South

Indian society?

The idol in the Vishnu temple at Yadugiri or Melakote

which is said to have been built by Vishnuvardhana at the behest of

Ramanujacharya, does indeed have the idol of a Sultani at its feet. There are

folk songs in Melakote that celebrate the love of Lord Vishnu for his “Sulatani”;

as well as legends of him going to see a Delhi princess for himself after

hearing of her beauty (258).

Historians say that there are similar folk narratives relating

to Tirupati in Andhra, and even the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai. It is said

that during the Cittirai festival in Madurai, when the marriage of Shiva to

Meenakshi is celebrated, Vishnu leaves his own temple of Vishnu Alakar to attend

the wedding. But learning that he had been misinformed as to the time of the

wedding, he gets annoyed, and instead goes to the Viraraghava Perumal temple

where he is joined by “Tulukka Nachchiyar” or “Sulatani”. Local tradition in

the South explicitly lists the Sultani as one of the wives of Lord Vishnu (258).

There are references in the literature to a “Gargya Gotra”, where “Gargya” is the patriarch of all “yavanas” – a term used for foreigners, including Muslims (257). In the temple at Srirangam there is a painted image of a woman identified as the Muslim consort of Lord Vishnu, called “Sulatani” or “Surathani” or “Tulukka Nachchiyar”.

The Vishnu idol here is offered roti – which is

associated with North India, and the Muslim diet. According to local tradition, the

Delhi Sultan donated lands to this temple. There is also a special festival in

which the Vishnu idol is brought to the painting to consort with Tulukka

Nachchiyar, dressed in a checked lungi. He is offered pan made in the manner that

is associated with Muslims (258). Incidentally, the Bedouin of the Arab deserts

wear a checked lungi till today, perhaps the legacy of the ancient Arab trade

in the cottons of Madurai.

The historian Richard H. Davies describes legends of

proposals of marriage to princesses of the Delhi Sultanate sent to the Rajput

Chauhan princes and the princes of Kampili, a kingdom of the upper Deccan (258).

The legend of Ramanujacharya continues as follows: Some

time had passed, and the Emperor of Delhi came to visit, bearing precious gifts

for the idol. His son, Kabir, accompanied him.

Kabir was so impressed with Ramanujacharya that he

stayed behind when the Emperor left for Delhi. But Ramanujacharya refused to

take him into his tutelage saying that Kabir was an outcaste - “mleccha”. But,

said Ramanujacharya, go to the Temple of Jagannath where mlecchas are

allowed to serve at the shrine. So Kabir went to Puri, and eventually Lord

Jagannath took him unto himself by leading him into the sea in the guise of a

dog.

None of this is historical: Ramanuja lived in the 11th

century – a long time before there was any Muslim Emperor in Delhi, and Kabir

was most likely a contemporary of Emperor Akbar’s. But the legends – which I found

in a book written in 1908 – speak volumes (255).

Whatever religious orthodoxy, zealotry and

over-protectiveness has existed in this land, there have also been equally

old and thriving parallel traditions of openness, inclusiveness and

inter-communal love.

Interestingly, there is a Kabir Panth – the Kabir

Chaura Math - based in Puri, the city of the Jagannath Temple, and there is a

Kabir legend attached to this temple. It is said that the King of Kalinga

(Odisha), Indrayumna (as mentioned above, there was a Ganga king here of the

name “Indra”, who built the Jagannath temple) had been frustrated five times in

the attempt to build a temple to Lord Jagannath. Each time the temple was

built, the sea would wash it away. So

Raja Indrayumna sought the help of the legendary Kabir who had come to Puri.

Kabir went to the seashore and drove his walking stick into the sand. Ever

since, the waters have stayed back, and the Jagannath Temple has been safe from

the sea (258A).

Syncretic Traditions

Kabir himself is a legendary figure of the North

Indian Bhakti movement, which came centuries after the Tamil one. Kabir is

claimed by both Hindus and Muslims to be from their community. The North Indian

Bhakti canon abounds with poems attributed to Kabir, exhorting Hindus and

Muslims to worship their gods instead of fighting over them.

When Kabir died, it is said that Hindus and Muslims

rioted over whether he should be given a Hindu or a Muslim funeral. In the end

it was decided that the body would be cut into two halves – one to be cremated

according to Hindu custom, and the other to be buried according to the Muslim

tradition. When the people entered Kabir’s spare hut to perform this grisly obeisance,

his body had disappeared, and in its place was a bed of flowers……

There are many such unexpected legends of Hindu-Muslim

friendship over idols. One, which locals tell me is being suppressed these days,

is the legend of Nathdwara. I have always wondered how the image of

Shreenathji, which depicts Krishna holding up Mount Govardhan, which is not in

Rajasthan but in Mathura, came to be worshipped in these parts.

This was the story as told to me: One day, the black idol of Shreenathji cut from the Govardhan mountain was discovered in the forests of Brindavan. In order to hide it from Emperor Aurangzeb, it was smuggled out of Mathura, hidden for 6 months in Agra, and then transported in a palanquin to the Raja of Mewar. The palanquin got stuck in the mud on the hill of Nathdwara. Taking this as a sign from above, the Raja built a temple and installed the idol of Shreenathji there.

The denizens of Nathdwara were Shaivites, and there was a Shiva temple in the vicinity. To honour Lord Shiva, bhog is offered first to Lord Shiva in the morning and only after that to Shreenathji. This tradition has been kept up to the present time. A wealthy local businessman has built a huge idol of Lord Shiva that is visible for miles around Nathdwara.

The fame of Shreenathji spread far and wide, reaching

Medina. Five pirs set out from there to see the wonder of Shreenathji for

themselves. They were accompanied by a lady - Chand Bibi.

The pirs were all enamoured of Shreenathji and decided

to make their home in Nathdwara, in order to be near him.

Chand Bibi was, if that were possible, even more

enamoured of Shreenathji than the pirs. Every evening, she would play chaupai (an

ancient form of chequers) with the Lord. One day she beat him, and Sreenathji

was so pleased that he told her to ask for a boon. I want nothing but to be

with you, said she. So Sreenathji decided that from then on, on one day of

the year, he would wear a “jama” (loose trousers), and not his usual dhoti in

honour of Chand Bibi.

In the old days, the convention was for Muslims to

wear stitched clothes whereas Hindus wore unstitched clothes, so the jama was

taken as a symbol of Islam and the dhoti as a symbol of Hinduism.

Even today, the artists of Nathdwara, famous for painting

beautiful images of Shreenathji in his different sringars (adornments),

traditionally include in their repertoire the image of Shreenathji in his jama.

I am told that prasad is sent till today from the temple to the five pirs of Nathdwara. The officiating priests in the Nathdwara temple, unusually, wear tall caps, and an angarakha (a stitched long shirt) over their dhotis. They are not bare chested as is usual in a Hindu temple for the officiating priests. The tall caps of the priests at Nathdwara are reminiscent of those worn by the officiating walis in North Indian dargahs.

Click here for Table of Contents and full paper

Comments

Post a Comment